Implementing a domain-specific language for interactive conversations (Part 1)

Author: Heikki Johannes Hildén

In our digital innovation work, we have created interactive listener experiences for a number of years now. A common theme in most of these solutions is the ability to engage the audience in conversations over some communication channel. With the help of mobile phones and other digital technologies we try to orchestrate 🎻 this in a way so that

- information and knowledge is shared across audiences, and

- insights can be gathered from the resulting data.

To us, these are the two main reasons for using digital technologies to extend the capabilities of radio.

📻 + 🤳 = 🙌

Recently, I spent some time thinking about this and ended up exploring a few ideas that may not be immediately useful, but nevertheless interesting. It occured to me that this notion of a “conversation” can be modeled as an Embedded Domain Specific Language (EDSL for short) — a language specialized to some application domain, and defined in terms of another (general purpose) programming language (usually referred to in the literature as the host language). For this purpose I chose Haskell, since it is particularly well-suited for DSL construction. Some familiarity with functional programming concepts and a language like Haskell, OCaml, Scala or Standard ML is therefore useful to be able to follow along.

Let's start with the following type:

data Action

= Send Message

| ReceiveThis is a coproduct or sum type with two data constructors.

The values of this type will be our building blocks for creating conversations. To keep it simple, we assume that Message is just an alias for String.

In a more realistic scenario, we could turn this into a container for content available in a number of different formats.

With the Action data type at our disposal we can (at least imagine 🦄 that we):

- send a message to the user; or

- listen for, and receive, some input (in a synchronous way).

At the end of this, we will be able to script out simple conversations using syntax like this:

send intro -- e.g., choose option 1 if you have a question

input <- receive

if (input == 1)

then do

question <- receive -- user provides their question (e.g., as a

-- text message or through a voice recording)

send outro -- thanks for your time

else

-- etc.The advantage of this approach (as I hope to show here) is that it allows us to use the Action primitive to build conversations in a way that abstracts from what we eventually do with them.

The code doesn't make any assumptions about how the user will interact with the program when it is executed.

To actually run the program, we need to provide an interpreter, which implements send and receive against a specific channel and technology platform.

The behavior of these commands, as experienced by the user, will depend entirely on the choice of this channel.

We could, for example, use the same program to represent the control-flow aspects of:

- An IVR script (using a third-party API or service like Twilio or Nexmo);

- A messenger application chatbot; or

- A USSD menu.

In the functional programming community, a popular technique for implementing domain-specific languages revolves around a construct known as the free monad (of a functor). A free structure is something that appears in abstract algebra and category theory, but this idea has proven to be useful also as a programming abstraction. We will get to what it means for a monad to be "free" in the next post, but let's first look at what it means for a monad to be… 🤔 a monad.

Sequencing actions 🧬

In code, how do we work with something like the sequence of instructions in the above program?

As a first attempt, we could try to represent it as a simple list.

Here is an example using our Action primitive:

[ Send "Hello and welcome. What is your name?"

, Receive

, Send "Thanks for chatting!"

]This is not a bad idea, but it lacks some expressiveness. As it turns out, Receive is pretty useless since there is no way to extract a return value from what we receive, and thereby allow subsequent commands to operate on input from the user. Here, two observations are in order:

Firstly; since we think of Receive as an effect of some sort — one which will also produce a result — the Action type is insufficient. We need to parameterize Action over the associated return value's type. So, for example, an Action Char is an action that returns a single character.

Using Haskell's (or rather the GHC compiler's) Generalized Algebraic Data Types (GADTs) syntax extension, the two constructors' type signatures can be made explicit in the following way:

data Action a where

Send :: Message -> Action ()

Receive :: Action InputSecondly; we need some mechanism for binding the result of an action to a name. Building on the previous example, we would then be able to do something like this:

send "Hello and welcome. What is your name?"

name <- receive

send ("Thanks for chatting " ++ name)So, instead of a simple list of instructions,

[ a :: Action

, b :: Action

, c :: Action

, ... ]we want something that looks more like…

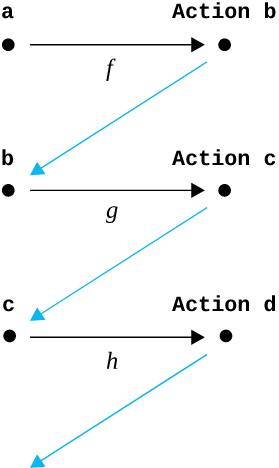

[ f :: (a -> Action b)

, g :: (b -> Action c)

, h :: (c -> Action d)

, ... ]But a list will not do the trick here — lists are homogeneous containers. What we need is some sort of function composition. Functions like these that return a value in some context are referred to as monadic functions and, as it happens, this is what Kleisli composition is all about.

If we add the ability to take “pure” values and bring them into the context (subject to some laws), then what we have is a monad.

From actions to programs

But we are getting ahead ourselves. There are really two different concerns involved here, namely:

- An expression grammar that captures our notion of a scripted conversation (the

Actiondata type). - Sequential composition of these expressions into programs in a way that also plays nicely with the type system.

To avoid proliferation of the Action type —

the purpose of which is to to describe individual elements (earlier referred to as the “building blocks”) of a conversation

— let's create a new data type called Program,

and instead think of Action values as the instructions of these programs.

To chain programs together we then need a function:

compose :: (a -> Program b) -> (b -> Program c) -> a -> Program cSo, in a nutshell 🌰 we have a bunch of functions x -> Program y that need to be glued together.

But what should the Program constructor look like here?

Let's imagine for a moment that these were ordinary functions a -> b, instead of a -> Program b.

Given functions f, g and h, we could then write

import Control.Arrow

prog = (\x -> f x)

>>> (\y -> g y)

>>> (\z -> h z)… where it is easiest to think of >>> as specialized to mean function composition in the opposite direction (i.e., flip (.)). So we could read this program as: f then g then h. The “snag” is that, since these lambdas do not share scope with the expressions earlier in the chain, if we'd want to access any of the intermediate results — consider for instance

frog = (\x -> f x)

>>> (\y -> g y)

>>> (\z -> h z)

>>> (\a -> (x, y, z, a))— then we're stuck with an error: Variable not in scope: x. This is similar to a problem that pops up in Promise chaining in JavaScript code:

doStuff()

.then(x => doMoreStuffWith(x))

.then(y => {

// where is my x?

});Our friend🦸here is the “reverse function application” operator, known as |> in OCaml and F#. This operator is available from Data.Function in Haskell, as (&), and succinctly defined as

x & f = f xUsing (&), we can rewrite our program as:

import Data.Function ((&))

grog = \x -> (f x -- parentheses added for emphasis

& \y -> (g y

& \z -> (h z

& \a -> (x, y, z, a))))The idea is that we arrive at the same (extensionally speaking, at least) function from \x -> (f x & \y -> g y) as we get from (\x -> f x) >>> (\y -> g y). As an example, here is how evaluation of 5 & (\x -> f x & (\y -> g y & (\z -> h z))) proceeds:

5 & (\x -> f x & (\y -> g y & (\z -> h z)))

(\x -> f x & (\y -> g y & (\z -> h z))) 5 -- x & f == f x

(f 5 & (\y -> g y & (\z -> h z))) -- normal order evaluation

(\y -> g y & (\z -> h z)) (f 5) -- same steps over again

(g (f 5) & (\z -> h z))

(\z -> h z) (g (f 5))

h (g (f 5))That's great, but we are not composing ordinary functions.

Instead of a -> (a -> b) -> b, we are now looking for something like Program a -> (a -> Program b) -> Program b.

Let's try to wrap this in a constructor.

data Program a where

Combine :: Program a -> (a -> Program b) -> Program bHmm… 🤔

To create a Program you first need a Program!

We'd better start with something else.

Programs should be built from instructions, i.e., Action values,

so I'll change the type of the first parameter to an Action a, and and arrive at this neat definition:

data Program a where

Combine :: Action a -> (a -> Program b) -> Program bTo create a Program we take an Action that produces a value of type a

and then Combine this with a continuation — a function that

takes the very same a value as input and returns another Program.

Note that we could just as well have defined Combine as t a -> (a -> Program t b) -> Program t b, where t is any type constructor * -> *.

We can now (almost) write our program as

program =

Send "Hello and welcome. What is your name?"

`Combine`

(\_ -> Receive

`Combine` (

(\name -> Send ("Thanks for chatting " ++ name)

`Combine`

(\_ -> ... ))))which also resonates with the lexical scoping rules of most procedural programming languages.

I wrote “…” in the last line because, at this point, there seems to be no way to terminate the program.

That is, in each step we are forced to provide yet another Program.

To get around this, we need to be able to create a “trivial program” that can serve as the base case. Adding a second constructor to Program solves this problem, and we can pretend that it's C and Exit the program with a return code 0:

data Program a where

Combine :: Action a -> (a -> Program b) -> Program b

Exit :: a -> Program a

program =

Send "Hello and welcome. What is your name?"

`Combine`

(\_ -> Receive

`Combine` (

(\name -> Send ("Thanks for chatting " ++ name)

`Combine`

(\_ -> Exit 0))))This is what I was referring earlier as injecting a pure value into the monad.

Next, let's create some recipes 🪄 for turning Actions into Programs:

send :: Message -> Program ()

send msg = Combine (Send msg) Exit

receive :: Program Input

receive = Combine Receive ExitWrapping up

We are now ready to revisit the function signature Program a -> (a -> Program b) -> Program b which is what we were initially looking for. Let's define this function as:

glue :: Program a -> (a -> Program b) -> Program b

glue (Combine action f) next = Combine action (\x -> glue (f x) next)

glue (Exit a) next = next aThis is just the >>= operator specialized to the Program type.

I can now go ahead and define Kleisli composition of Programs, in terms of this function.

compose :: (a -> Program b) -> (b -> Program c) -> (a -> Program c)

compose f g = \x -> glue (f x) gAll we need at this point to be able to use Haskell's do-syntax in the convenient imperative style

is to make Program an instance of the Monad typeclass.

Combine action prog >>= next = Combine action (\a -> prog a >>= next)

Exit a >>= next = next a

return = ExitIn the final program, I have also provided instances of Functor, and Applicative. These are requried since Monad is a subclass of Applicative which, in turn, is a subclass of Functor.

With recent versions of ghc, the Functor typeclass instance can be derived automatically by the compiler.

A command-line interpreter

To make it possible to run this program, I am going to create a simple IO interpreter which uses putStrLn and getLine to interact with the user.

Not too exciting, but bear 🐻 with me.

{-# LANGUAGE GADTs #-}

module Main where

type Message = String

type Input = String

data Action a where

Send :: Message -> Action ()

Receive :: Action Input

data Program a where

Combine :: Action a -> (a -> Program b) -> Program b

Exit :: a -> Program a

instance Functor Program where

fmap f (Combine action prog) = Combine action (fmap f . prog)

fmap f (Exit a) = Exit (f a)

instance Applicative Program where

(<*>) (Combine action prog) arg = Combine action (\a -> prog a <*> arg)

(<*>) (Exit f) arg = fmap f arg

pure = Exit

instance Monad Program where

(>>=) (Combine action prog) next = Combine action (\a -> prog a >>= next)

(>>=) (Exit a) next = next a

send :: Message -> Program ()

send msg = Combine (Send msg) Exit

receive :: Program Input

receive = Combine Receive Exit

program :: Program ()

program = do

send "Hello and welcome. What is your name?"

name <- receive

send ("Thanks for chatting " ++ name)

interpret :: Program a -> IO a

interpret (Exit a) = return a

interpret (Combine action p) =

case action of

Send msg -> do

putStrLn msg

interpret (p ())

Receive -> do

input <- getLine

interpret (p input)

main = interpret programRun it

Run this program directly in your browser on repl.it.

This was a lot of work, but it pays off in the end. In the next post we'll explore and make use of a special property of this monad which will let us get rid of some of the boilerplate and make the code more elegant 🎩. We will also develop some more practical interpreters that let us interact with the user in more interesting ways. Until then!